Timeline of Early American Art: Art History 101

A brief history of art in the pre-Columbian Americas

The Americas are often ignored in conversations about early art. The mainstream view says they were uninhabited for most of human history.

There’s wide disagreement over when and how the Americas were settled. Humans could’ve moved into the Americas anywhere between 50,000 and 10,000 years ago. Maybe earlier. Archeological evidence is inconclusive and incomplete.

What people are familiar with is the “Clovis first” theory since it’s taught in grade schools. Nomadic hunter-gatherers walked across the Bering Land Bridge when there were passages through the ice covering a large swathe of the continent. The bridge existed from 45,000 to 12,000 BC, with ice-free valleys appearing in the later stages of this time range. The Clovis culture was thought to be the first major culture to populate the Americas, after 14,000 BC.

Over the past 10-20 years, this theory has been questioned more and more. Dozens of archeological sites have artifacts that can be dated to 20,000 BC or 30,000 BC or even older. The disputed Cerutti Mastodon site even goes back to 129,000 BC.

Many archaeologists now believe the Americas were settled by boat. The “land bridge” hypothesis may have happened concurrently, or in conjunction, or not at all.

In any case, we have little surviving art from so long ago. It’s mostly small stone or bone tools. These early Americans didn’t have writing, megaliths, or other obvious markers of civilization.

North America

The climate stabilized in 8000-7000 BC, allowing early societies to flourish and expand.

Mound building became popular after 4000-3500 BC and is clear evidence of complex societies. Well-known structures include those at Watson Brake (3500 BC), Poverty Point (1700-1100 BC), Serpent Mound (sometime before 300-100 BC), and Moundville (1000 AD).

Early groups generally fall under the “Woodland period” of 1000 BC to 1000 AD. This was a period after hunter-gatherers transitioned to agriculture (1850 BC). Pottery became more widespread as culture and technology advanced.

One early culture was that of the Hopewell, from 200-100 BC to 500 AD. They built large mounds and had a wide variety of art. They created pipes, pottery, necklaces, statues, and other pieces, sometimes using exotic materials like shark teeth and silver. (Note: the Hopewell weren’t exactly a single culture; they were multiple groups which shared some traditions and a large trade network.)

Between 500 and 1000 AD, it becomes more difficult to discuss specific major cultures. Communities spread out and developed their own unique cultures, trading with each other less often, and creating a fragmented landscape with hundreds of different tribes. The modern-day Canadian government recognizes over 600 “First Nations” and the United States recognizes slightly fewer.

North American “cultural areas” can be roughly divided into 10 categories.

Alternatively, they can be organized by language families, but that makes it more complicated.

Either way, it’s difficult to give a broad overview of Native American art, given the sheer variety of cultural spheres of influence.

Some quick examples:

Tribes in the Great Plains made extensive use of beads, feathers, and leather.

Well-known tribal groups in the southwest include the Apache and Navajo, who shared ancestors that entered the region by 1400 AD. While the Apache remained nomadic, the Navajo turned to farming, which they adopted from the Pueblo people.

The Pueblo (Anasazi) Mesa Verde cliff dwellings were built between 1000 and 1300 AD. Some walls, and pottery, were decorated with simple geometric designs. Despite the complexity of the settlement and erecting over 600 buildings, the site was soon abandoned, and the Pueblo migrated further south. Drought is thought to be the main culprit.

Around 1000 AD, Nordic explorers discovered North America (Vinland).

The Woodland period is followed by the Mississippian cultures (mostly 800-1500 AD), which included the Fort Ancient culture and Plaquemine culture, among others. The Mississippians built large pyramid-like mounds. Their ancient city of Cahokia included over 100, including the titanic Monk’s Mound which is considered the largest American pyramid north of Mexico. The area was abandoned around 1350 AD. Since they didn’t develop writing, speculation abounds as to why. It was likely related to climate and/or politics, since no evidence of war has been found.

Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean in 1492, which launched many subsequent voyages to the Americas, including those of Amerigo Vespucci (1499), Hernán Cortés (1519), and Francisco Pizarro (1524).

Central America (Mesoamerica)

Early Mesoamerica (Preclassic & Classic)

Early Mesoamerica (commonly given as 18,000 to 8,000 BC) is characterized by hunter-gatherer tribes and zero pottery. Thus, no art.

Agriculture and permanent settlements began appearing around 3,500 BC, if not earlier. Pottery was introduced around 2300 BC and slowly replaced stone. Initial designs were modeled after early natural vessels like gourds. Since the wheel wasn’t a thing here, they shaped clay by hand and/or used molds. There’s evidence that textiles were woven in 1800-1400 BC.

The first major ancient culture was the Olmecs (1500-400 BC), “known as the ‘mother culture’ of Mesoamerica.” Unfortunately, they didn’t have writing, so much of their history is speculative. Most buildings haven’t survived to the present day either. They used earth and clay to build their settlements, keeping stone only for sculpture.

The Olmec are best known for their colossal stone heads with helmets. Other art includes figurines and jade face masks. They allegedly invented a complex calendar, the famous Mesoamerican ballgame, the number zero, and bloodletting.

In 400-350 BC, Olmec civilization went into sudden and steep decline. Likely from environmental changes such as drought, earthquakes, and/or volcanic eruptions.

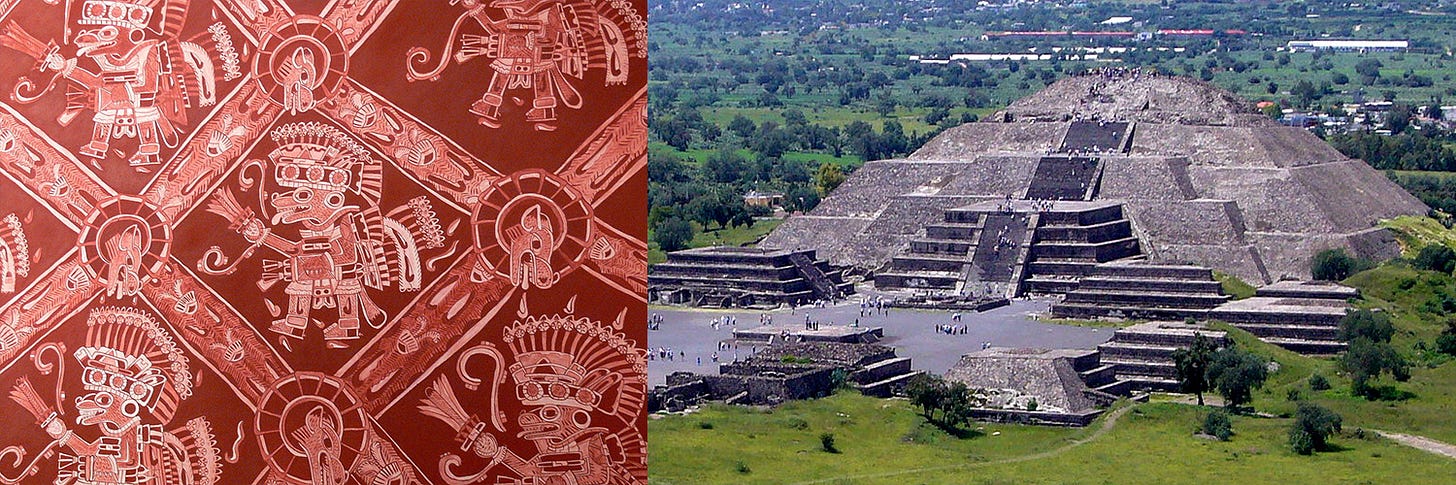

Teotihuacan rose in power around this time. Archeological evidence shows that the area began as a collection of small villages in 600-200 BC. Over the next few hundred years, a massive city developed, including some of the world’s largest structures. They’re known for their incredible pyramids, along with murals and obsidian trading. The center of their empire is thought to be the largest city in the Americas at its height (350-650 AD). Like the Olmecs, they didn’t have writing.

Teotihuacan declined in 650-750 AD, in the midst of unknown conflict(s). Speculation says it was a civil war or other uprising; several areas were burned and sacked. Other cultures soon came to prominence in their wake, including the Coyotlatelco and the Toltec culture (which reached its peak in 950-1150 AD).

The Zapotec civilization began around 700-500 BC in southern Mexico (modern-day Oaxaca). They’re well-known for their cities of Mitla and Monte Albán. They continued until about 1500 AD, when Zapotecs came into conflict with the Aztec Empire; the Spanish conquistadors swept through soon after, and defeated the Zapotecs by 1527.

The Great Pyramid of Cholula (Tlachihualtepetl), the world’s largest pyramid by volume, was built in multiple (4-6) stages. It began with a small building in 300-200 BC. Typical for the time, its murals were initially painted only with red pigments.

El Tajín of the Veracruz culture (100-1000 AD) was at its height between 600-800 and 1200 AD. It was an important trade center influenced by the Olmecs and Teotihuacan. Their architecture differed from other Mesoamerican cultures, including the use of cement roofs and decorative niches. It’s not clear what caused the downfall of El Tajín. It’s thought that the city was invaded, burned, and abandoned.

Mayan Culture

The famous Maya civilization is one of the oldest. Small villages dotted the Yucatán Peninsula and surrounding areas as early as 8000-3000 BC. The first complex societies rose after 2000 BC, beginning the “Preclassic Mayan” period, where villages coalesced into cities (generally independent city-states–there was never a “Mayan Empire”). Archeological efforts are ongoing, and we currently believe 750 BC is when the first major cities arose. Causeways and pyramids were built even at early sites like Nakbe and El Mirador.

Tikal was likewise inhabited early, with major construction efforts coming later. Its pyramids and platforms began construction in 400-300 BC. This is also when the Mayans began using a hieroglyphic-style writing system.

Their art is mature and complex, with well-defined techniques alongside a variety of materials and aims.

Calakmul, the “Snake Kingdom,” was one of the largest Mayan powers. In the Late Classic (600-900 AD) it was thought to control a population of 1.75 million people. Their main rival was Tikal, with conflicts taking place in 537-838 AD.

“Classic” Mayan culture, their height of accomplishment, is categorized as 250-900 AD. The Mayan civilization went into steep decline around 800-900 AD. Called the Classic Maya collapse, it’s “one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in archaeology,” much like the European Bronze Age Collapse. Several factors may have gone into the Mayan collapse, and speculation is abundant: disease, drought, invasion, etc.

Other important Mayan sites include:

Postclassic Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica’s “Postclassic Period” (900-1521 AD) is the final few centuries before the Spanish encountered the Aztec and Maya peoples.

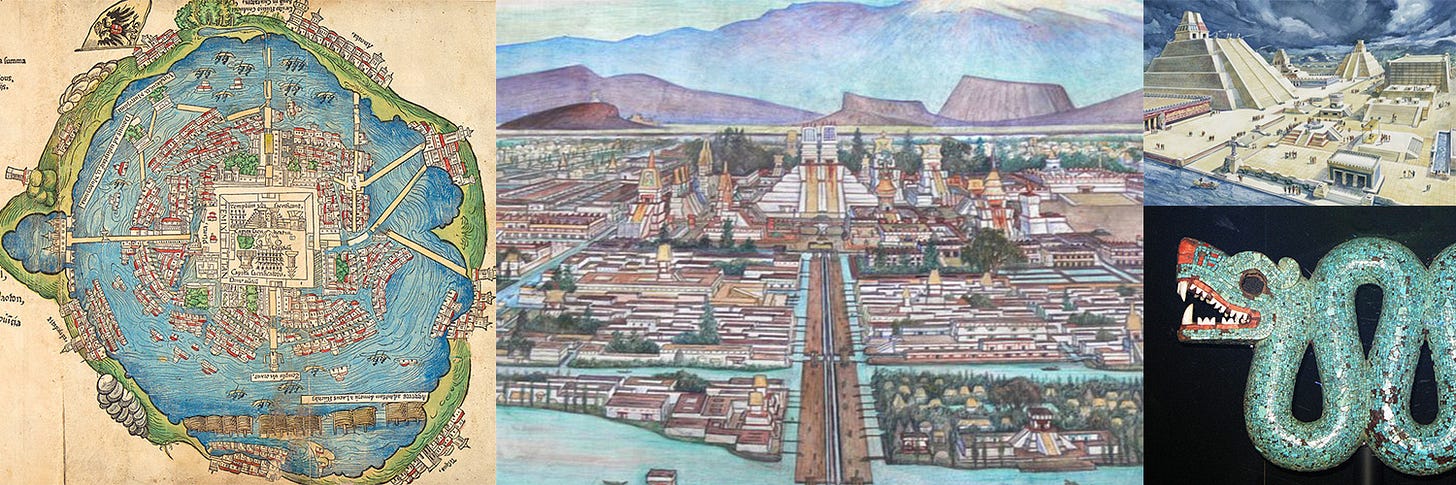

The Aztecs (Mexica) began as a semi-nomadic mercenary tribe traveling south from the present-day American Southwest. (Note: The Aztecs rewrote their own history, so their true origins are unverified.) They made their way down into central Mexico around 1250 AD. In 1325 they founded what would become their capital, the tremendous city Tenochtitlan. The Aztecs grew in power through forming alliances and their experience in warfare. The beginning of the Aztec Empire is assigned to 1427 AD. At the heart of that empire was a vibrant and complex culture of controversial artistic accomplishments.

The Aztec capital had gardens, farms, man-made islands, levees, drawbridges, aqueducts, bottled water, sanitation workers, saunas, a free-trade market, a police force, a zoo, an aquarium, a museum, temples, etc. They also had schools, including a music school, and the equivalent of an opera house. Flowers, statues, and works of art decorated the streets. The king’s palace had hundreds of rooms, including rooms for visiting nobles or ambassadors. The Spanish called Tenochtitlan the “Venice of the New World.”

Aztecs assigned great importance to poetry and music, and everyone was expected to memorize at least one poem. Their children were taught both art and war, literal warrior-poets. The most famous Aztec poet was the warrior-king Nezahualcoyotl of Texcoco. He was a scholar, architect, engineer, artist, and more.

The Codex Mendoza is one of many sources on Aztec life and history. One of the most famous pieces of Aztec art is the stone calendar of Tenochtitlan, a 12-ton stone disk called the Sun Stone.

For almost a century, the Aztecs controlled a large portion of Mexico, until Hernán Cortés led the collapse of their empire in 1521.

It’s an odd dichotomy—the Aztecs were brutal warriors, famed for human sacrifice and towers of skulls. And yet they had some of the greatest artistic ambitions in the Americas, while known among rivals for their elaborate flowery speech (which allegedly gave the Spaniards’ translators a hard time).

As for the Mayans? After the Classic Maya collapse diminished their power, they were largely a scattered culture split into warring kingdoms. Chichen Itza benefited, at first, from the decline of other regional powers. They were the dominant power for almost 200 years until their own decline, around 1050-1100 AD.

The Mayan people first came into contact with the Spanish in 1502 and 1511. Hernán Cortés heard of the Aztecs through the Maya, setting the future fall of Tenochtitlan in motion. Even though the Mayans lacked a central power, the Spanish reported that they were wealthy and thriving, comparing their art and architecture to the Egyptians.

The Spanish began their Yucatán colonization efforts in 1527, subjugating a large portion of the peninsula over the years. When they launched their final assault in the 1600s, just one kingdom remained. The last independent Mayan capital fell in 1697.

Because the Mayan culture was so fractured, it took the Spanish longer to conquer them than the Aztecs. Some Mayan culture survives to the present day.

South America

South America was theoretically the last region of the Americas to be settled. Still, like northern sites, we don’t know exactly when or how. It’s thought that human habitation began around 15,000 BC (and of course this is disputed).

Andean South America

The areas around the Andes mountains (the world’s longest continental mountain range) gave rise to the continent’s most famous civilizations, including the Inca.

Plants were domesticated in South America between 8000 and 5000 BC, including potatoes. Llamas and alpacas were kept as both a source of wool and as pack animals. The environment played a large role in how civilizations developed.

Large-scale agriculture began sometime around 3500 BC. Villages and cities followed, along with early platform mounds and temples. Pottery was invented in the Andes around 2000 BC.

The city of Caral, according to some, is the oldest city in the Americas and founded in 3500 BC. The Caral-Supe civilization (Norte Chico) invented Quipu, a mysterious record-keeping system which used knotted and colored strings to convey information. The later Incan Empire used it instead of writing.

Unusually, visual arts are few at Caral. It seems the people preferred music as their art form of choice, alongside their textiles and architecture (conspicuously absent of carvings or stucco).

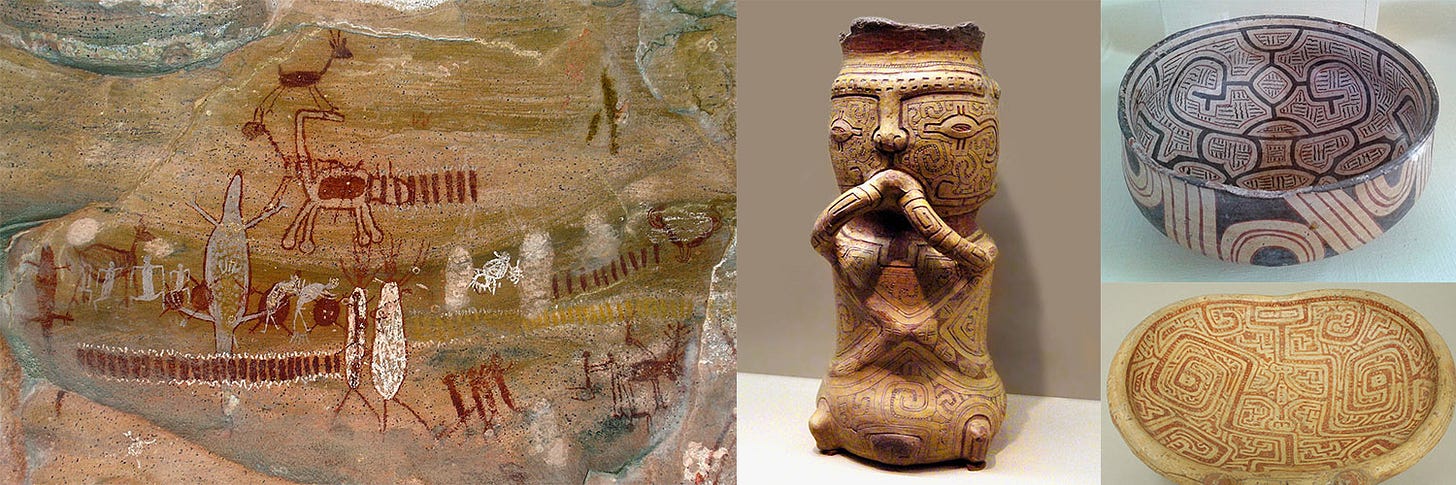

The next major culture was the Chavín, emerging near the Peruvian coastline around 1000 BC. Like the Caral culture, they didn’t have a writing system, but they did have elaborate art and architecture. Their style influenced other cultures in the Andes, leading to a recognizable regional style similar to Mesoamerican art.

The Muisca culture began emerging around the same time, in modern-day Colombia. They had agriculture and pottery, organizing into a loose confederation of tribes by 800 AD. Their varied and complex art includes significant goldworking, which led to the legend of El Dorado. A Muisca ruler (zipa) would allegedly enter Lake Guatavita with gold dust on his body as part of a ritual. Somehow this became our modern story about a city made of gold. The Spanish conquered the Muisca by 1537-1540, and they still exist today. With their long history and accomplishments, they’re thought of as the fourth most important pre-Columbian civilization (after the Maya, Aztec, and Inca).

The Paracas culture (800-100 BC) is known for their shaft tombs and mummies, along with their skill in textile weaving and water management. Their mummies were buried with elaborate textile wrappings and jewelry, which calls to mind the Egyptians.

The Nazca culture either evolved from Paracas or was strongly influenced by it. They’re best known for their underground aqueducts (puquios) and the Nazca Lines, in the deserts of southern Peru, created between 500 BC and 500 AD. Nobody knows the purpose of the lines; they may point to water sources or various pathways, or serve an astronomical or religious function. It seems they were constructed with rope and wooden posts, a relatively quick and simple method which could be accomplished with just a few people. The culture went into decline after 500, vanishing by 750 AD.

Other kingdoms and cultures rose and fell over time, including the Moche culture (100-700 AD) and Chimú Empire (Chimor Kingdom). The Tiwanaku Empire and Wari Empire both fell around 1100 AD. The Tiwanaku are probably best known for Pumapunku in modern-day Bolivia.

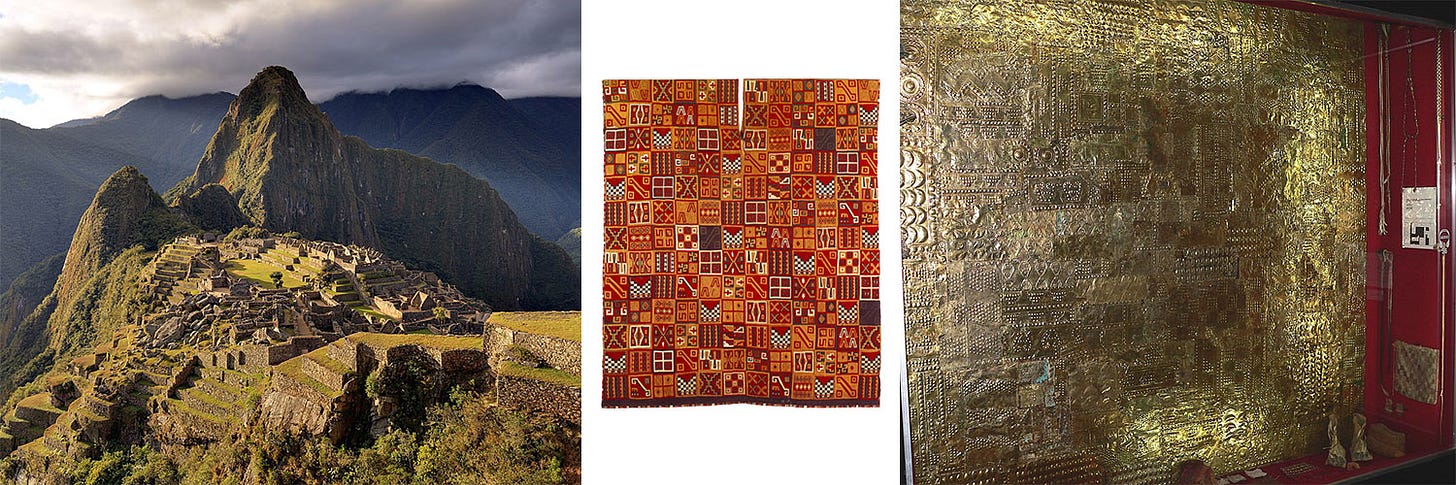

Then, from the city of Cusco, came the Inca Empire. They began expanding in 1438, and within 100 years, controlled the largest empire in the Americas.

Although the Inca didn’t invent the wheel or have an Iron Age, they built an extensive civilization and road network.

Machu Picchu is one of the most recognizable archeological sites in the world. It was built around 1450, possibly as a large royal estate. It’s thought that 750 people lived there among 200 buildings.

A civil war broke out among the Inca in 1529 after arguments over who would take the throne: Huáscar or Atahualpa. While the latter won, the Spanish–led by Francisco Pizarro–captured him soon after, in 1532. After 40 more years of fighting, the last monarch of the empire was killed by the Spanish in 1572.

Non-Andean South America

This region of the world is one of the toughest to do archeology in, mostly because of the size and density of the Amazon rainforest. Many potential sites have been overtaken by the jungle as nature reclaims its own. We don’t know much about eastern South America, especially compared to other regions of the Americas.

Some reported archeological evidence of human activity confusingly predates evidence from North America and Mesoamerica. UNESCO says Serra da Capivara National Park has cave paintings more than 25,000 years old, and some paintings may go back to 48,000 BC.

Early cultures included the Marajoara, and the people of Kuhikugu which may have inspired the “Lost City of Z.” Both built earthwork mounds and their societies collapsed before the Portuguese met them.

Eastern South America didn’t develop the same art, architecture, or agricultural habits as the Andean regions. Tribes had pottery, created geoglyphs, cultivated plants, used “terra preta” (black earth), and more. Yet remained largely semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers throughout history.

Today, it’s widely known that many indigenous groups (estimated at 400+) inhabit the Amazon Basin, and some (estimated at 100) have never come into contact with Europeans or their descendants.

In 1500 AD, Pedro Álvares Cabral claimed Brazil for Portugal. It’s thought that disease became widespread soon after, killing many indigenous groups who had no immunity toward them. Estimates range into the millions.

The Spanish explorer Francisco de Orellana was the first European to sail the Amazon river across the continent. Friar Gaspar de Carvajal documented this trip, reporting signs of vast civilizations. Modern-day LIDAR may corroborate this.

Closing Thoughts

Early American art was vibrant, with parallels with other cultures throughout history. I couldn’t get to literally everything (this is already one of my longest-ever Substack articles) but this can easily be a launchpad for doing further research.

What’s interesting is the apparent human need to stack dirt and stone. Most major cultures practiced some form of mound building, if not outright building pyramids. This is true even of cultures that had no known contact with each other.

Contact with Europe brought a period of upheaval as the Baroque style dominated the globe. Native artistic styles were diminished in favor of what was popular among the Spanish. This remained the case until wars of independence broke out across the Americas, like in Mexico (1810-1821) and further south. Simón Bolívar, the “Liberator of America,” led much of South America to independence (1811-1826).

In modern times, descendants of indigenous Americans (and others) have attempted to revive certain styles and techniques.

This is a reader-supported publication. For further support of my work:

I sell physical artwork at ApolloGallery.org with more to come

You can hire me for graphic design work